It’s that time again…

Take a deep breath. Gird your loins. It’s time to commission a new market segmentation: one of the most important investments an insights team can make. But also one of the most challenging to get right and (whisper it) not always guaranteed to deliver ROI.

Done well and, crucially, applied effectively, segmentation is one of the most versatile tools in the insights kit. Segmentation has benefits for teams throughout the organisation and contributes to innovation, communications, growth strategy, communications, customer service – it can even drive cultural change towards consumer centricity.

However, at The Forge, we sometimes get to work with insight professionals who have been disappointed by previous investments in segmentation. We have a hypothesis about why this happens and, based on this, we’ve been using an approach – reverse segmentation – that reduces the risk and maximises the return.

This is timely; we are seeing a lot of interest in new segmentations right now. We’ve just lived through Covid and we’re still living through the cost-of-living crisis. These global events have changed how consumers feel, what they believe and how they act, and brands are keen to understand how these changes are playing out. Segmentations are often said to last between three and five years, so anything built before Covid is now looking seriously out of date.

Good segmentation is attitudinal, right?

It is generally felt that is that there is little insight to be derived from post-hoc segmentations based purely on demographics or user characteristics. This is because they can be a bit simplistic and rely too much on hypothesis, or even on unverified stereotypes. For example, brands often want to target Gen Z without understanding first whether they differ from other age groups in how they interact with the category and, second, whether they are sufficiently homogenous as a group.

Similarly, it is superficially attractive to split the market into non, low, medium and heavy users. But in practice you can end up with a ‘chicken and egg’ situation: you only learn that heavy users really like the product or the brand, and non-users don’t, which makes the segmentation hard to apply in practical terms. More nuance is required.

The received wisdom is that if you conduct a priori attitudinal segmentation you get to the heart of what drives differences in behaviour. And this is true, up to a point. We have worked with brands that have segmentations where the solutions are purely attitudinal and not clearly differentiated by demographics or category behaviour.

For example, if you segment people according to attitudes to cooking, you may find that your ‘Keen to Cook’ segment is spread fairly evenly across age and gender groups, as a love of cooking isn’t strongly associated with a particular demographic; your ‘Tried and Tested’ and ‘Ready-meal Rebels’ segments may well be similarly distributed.

So what is the problem?

Our hypothesis is that in some (but not all) situations, brands find it hard to get value from segmentations that are based entirely on attitudes, and that are not well-differentiated by demographics or by category or brand usage. We believe there are three potential pitfalls with these types of segmentations.

- Purely attitudinal segmentations can be hard to visualise. Without a clear and demographically differentiated persona for each segment, it can be difficult for stakeholders in marketing, sales, comms and innovation teams to make sense of and know how to apply the segments. In practice, you often need to try and sum up your segments in just two or three words, so you can socialise them effectively throughout the organisation, and this isn’t easy to do when segments incorporate a range of different attitudinal axes. And those words are critical: stakeholders often don’t have the time, skills or inclination to dive into the data and absorb the segment profiles themselves. This is even more of an issue in segmentations that span a broad range of markets, including ones where English isn’t spoken as a first language.

- Purely attitudinal segmentations can be difficult for brand managers to use if there isn’t much distinction in which segments use the brand or have the specific needs (such as sensitive skin or dietary requirements) that the brand addresses. Often, brand positioning will already have a slant towards a certain demographic, such as teens, mums or retired people. If the segmentation doesn’t at least partly align to demographics, it’s hard to know how to use it.

- Purely attitudinal segmentations make it hard to target and reach your priority segments. Without a clear demographic profile, it’s not possible to buy media to target your priority segments, which means that although you can use the insights from the segmentation to help you develop comms, when it comes to implementing a campaign, you can get stuck.

The answer? Reverse segmentation

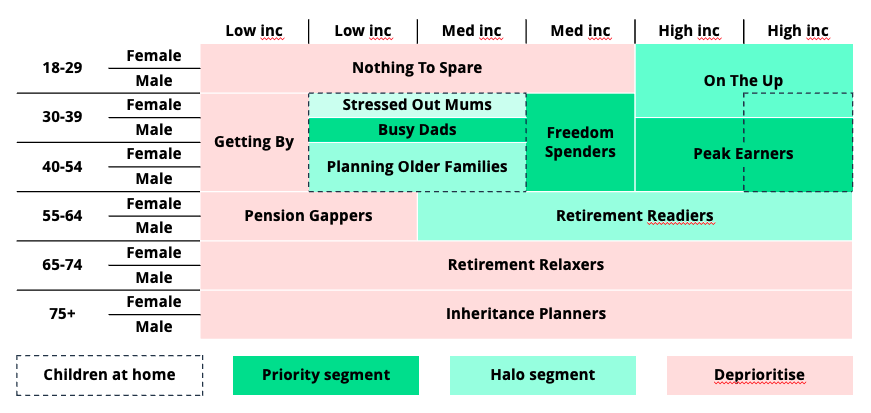

We don’t want to throw the baby of attitudinal insights out with the bathwater of lack of demographic or behavioural specificity. So, we believe the answer is to combine all these elements in a process we call reverse segmentation: segmentation driven by attitudes and category behaviour but defined on known quantities such as demographics. This is the reverse of how you would traditionally present an attitudinal segmentation where the demographics are ‘hidden’ in the profiling. This isn’t a new idea, but it is not as widely used as we believe it should be. Our (invented and overly simple) example below, in the financial services sector, shows the sort of segmentation you can derive when you combine attitudes and demographics this way. Segment names are descriptive and based partly on attitudes, so are easy to understand while, crucially, targetable in terms of age, gender and life stage.

Is reverse segmentation right for your brand?

This sort of segmentation isn’t appropriate – or necessary – in every circumstance. If you are purely looking to understand how consumers divide around a specific issue, or using your segmentation entirely in innovation and for creative stimulation, then it matters less if your segmentation is purely attitudinal. However, for a truly versatile, hard-working segmentation that has longevity and can be applied tactically to campaigns as well as strategically and creatively, we’d argue it is worth considering this approach.

If the following criteria apply, then you should consider a reverse segmentation approach.

- You have a need to gain more insights about your audience than would be available through a purely demographic or category behaviour segmentation.

- Your brand is in a mass-market category and isn’t trying to appeal to a niche audience. If you are after, for example, the most eco-conscious, the most fashionable or the most tech-forward fraction of the population, then defining your target segment on that attitude is workable as they are reachable in a practical sense.

- You have a starting hypothesis that behaviours align well with demographics or other targetable characteristics. For example, we conducted a segmentation in a haircare category that was driven by attitudes to haircare and grooming, in which segments were defined not only by age and gender but also by hair type. The data enabled us to test our hypotheses about the links between these attributes, and category attitudes and behaviour.

It is worth noting that, like any segmentation, reverse segmentation is a mixture of art and science; getting to the segment solution will be an iterative process and you don’t have to commit to this type of approach at the start of the project – the survey will be the same either way.

If you would like to know more about how this might work for your brand, please get in touch.